Written by: Jeffries F. Epps, Staff Writer

Over the past decade, STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) education has been at the forefront of education reform, with a heavy emphasis on the “T”—technology. Schools and educational institutions have poured billions into high-tech tools such as robots, electronics kits, and software to prepare students for the future workforce. According to a Global News Wire report, the Global K-12 Education Technology Spend Market was valued at a staggering $8 billion in 2022. However, in 2024, education faces new challenges, including teacher retention and the relentless pace of technological change.

While the introduction of advanced technology into classrooms is commendable, many educators and institutions may be missing the mark. Often, the focus is on teaching the technology itself rather than using technology as a tool to facilitate deeper learning. The rapid turnover in technology and the overwhelming focus on “the new” often distracts from the primary goal of education—engaging students in meaningful, effective learning experiences.

At STEMERALD City, a different approach is championed. Instead of centering the curriculum on technology, STEMERALD City’s methodology integrates technology into the broader STEM framework, using it as a tool rather than the focus. In one of their 3-hour sessions, a student experienced hands-on learning using three different technologies—physical computing, ground-based drones, and indoor aerial drones.

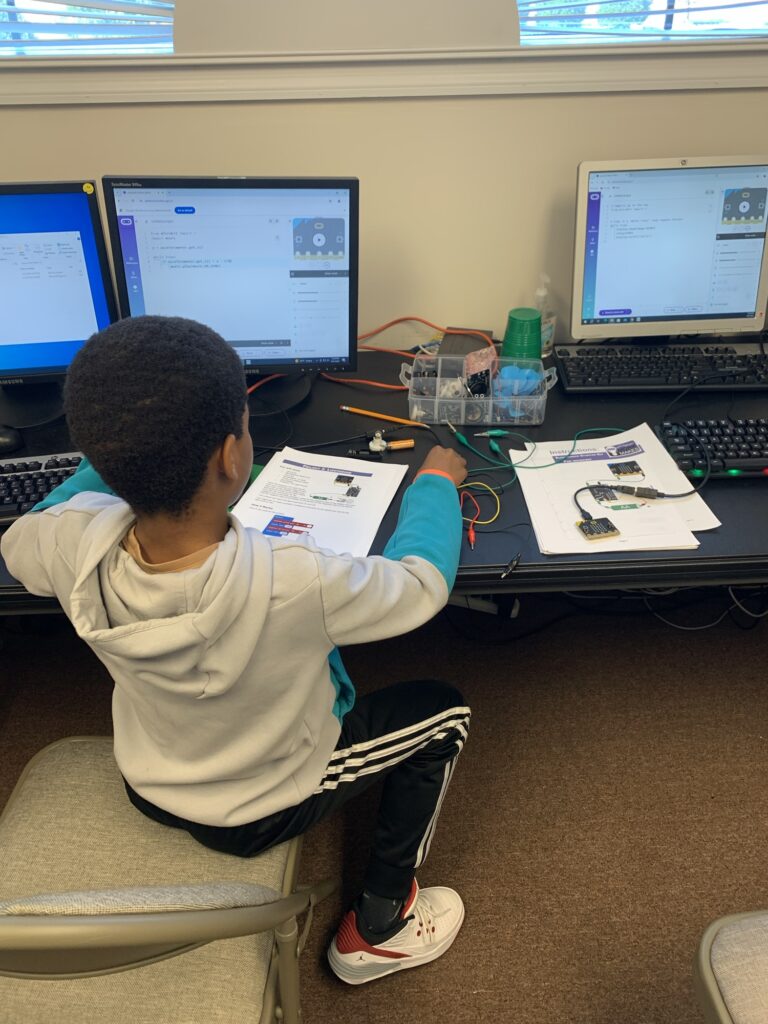

The session’s first activity introduced physical computing with the Microbit, combining coding and electronics. The student worked with wiring diagrams, alligator clips, circuit boards, and blocks of Python code. By making physical connections and experimenting with the code, the student didn’t just learn programming; they explored how electricity is distributed across circuits. This was the “S” in STEM at work, reinforcing scientific principles through technology.

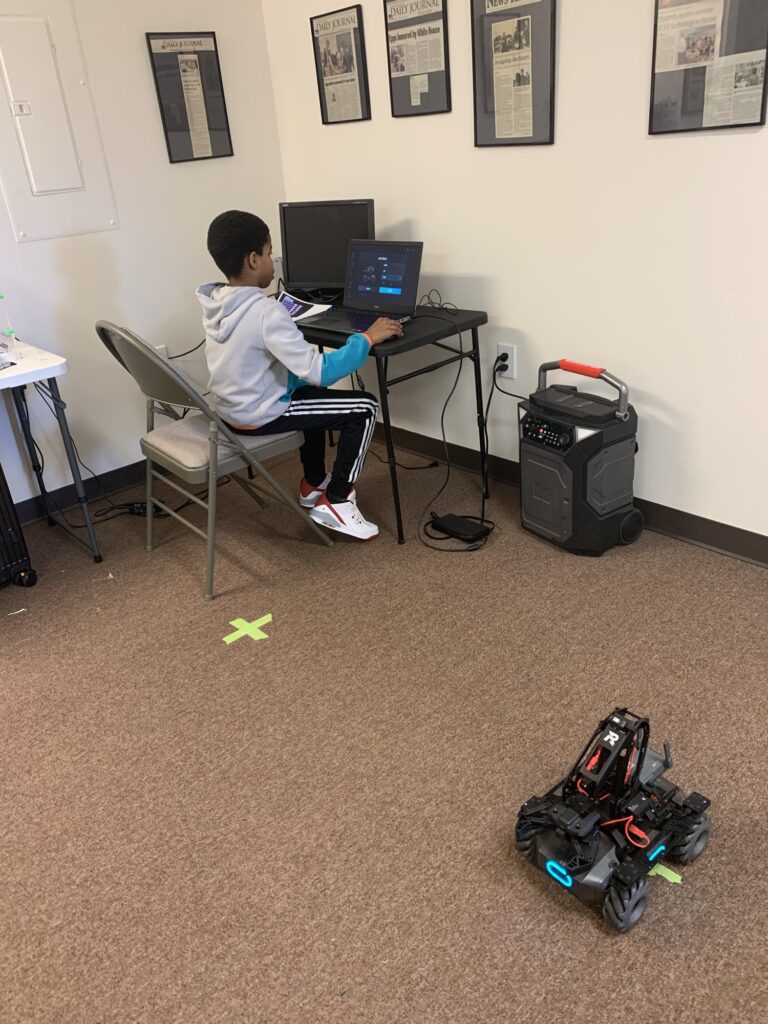

From there, the student unknowingly applied the engineering process by adjusting and modifying the circuits to achieve desired outcomes. Changing variables in the code brought the “M” in STEM to life, as the student saw firsthand how math played a crucial role in the robot’s performance. The ground-based robot and drone activities followed the same principles, with the student observing how the distribution of electricity influenced speed and functionality.

While three different technologies were used, the overarching learning objective remained clear—understanding electricity and its applications. The technology wasn’t the star of the show but a tool to make abstract concepts tangible and relatable.

The lesson here is critical: technology in the classroom should be selected based on its ability to address diverse learning styles and make complex objectives more accessible. It doesn’t have to be the latest gadget or the flashiest software. Good technology is effective when it’s easy to use, supports the learning goals, and meets students where they are.

As the pace of technological innovation continues to accelerate, schools and educators should refocus on using technology to teach—not teaching technology. When combined thoughtfully with science, engineering, and mathematics, technology becomes a powerful vehicle for higher student achievement.

In today’s classrooms, the T in STEM should not overshadow the rest; it should serve as the bridge to understanding, bringing learning to life.